This is the real-life story of a client, a VP at a national financial services business, who found 3 concrete steps to change poor relations with his peers on the leadership team.

Phil (not his real name) experiences personal friction with his senior leadership colleagues because they:

- often revisit their decisions

- agree with the plan but then do something else

- don’t give him input on his projects even when he asks for it, but complain later about what he does

This frustrates Phil, who has all the qualities of an exceptional performer. He’s:

- clear, decisive and direct

- quick-moving but also strategic

- often the smartest person in the room.

Phil was stuck in classic high-performer arrogance: “Just let me explain it to you,” “Just let me do it.” But Phil’s colleagues aren’t dolts, and he’ not a jerk. He has enough humility to see his part in the problem and he decided that he wants to practice what he calls a “softer directness.” Over the 5 months we’ve been working together, here’s what he did.

First Question: What’s the biggest trouble trigger?

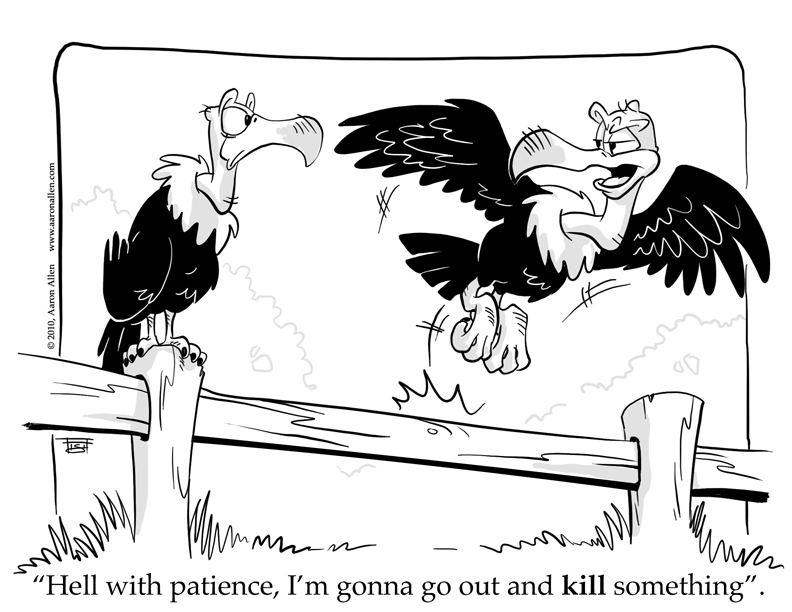

Phil looked at when he gets into interpersonal trouble, and saw that his biggest trigger was impatience. Others don’t always move as fast as he does. Some talk things through more before they understand. Some examine all sides. Some dig deep enough to know that everyone is truly agreed, not just acquiescing. To Phil, this is time-wasting inefficiency. “Let’s get on with it.”

Step 1: Find value in the process

Phil accepted that his impatience doesn’t change anyone’s temperament, but it does make people not want to listen to him and not want to tell him what they think. His attachment to “get on with it” is a blind spot, too narrow a definition of “results.” It makes true agreement impossible.

The process of interaction that he calls inefficient is the process that builds strong teams, and a strong team is the most important result of all.

So Phil is giving more space for the process of his interactions with his peers. He’s noticing his impatience as it arises and he’s taking a breath and listening. People aren’t on edge around him anymore so they don’t hide their thoughts. He’s letting himself be curious enough to get out of his blind spot and learn how the process itself is a valuable result.

(For more on mistaking efficiency for results, click here.)

Step 2: Ask, don’t tell

Phil understands things quickly, and is particularly good at seeing how specific efforts do and don’t serve the larger purpose. When other people don’t, he tells them. He may be right, but in a team right isn’t enough

Phil describes this as “wielding clarity,” but people don’t like having something wielded at them. They resent being told, and because they haven’t themselves been through the mental process of understanding, they don’t really trust or accept what they’re told. They also don’t build their own capacity to see the bigger picture.

So Phil has stopped telling, and asks instead. This is tricky. His questions have to not be veiled statements. He has to intend to draw out the understanding of his colleagues, not make himself look smart. But asking, “How does this fit with X?” is very different from saying, “This will never work with X.” Especially if the tone of the question makes it clear that Phil actually wants to know what the other person thinks. Achieving this tone is a great way for Phil to practice being part of a fruitful discussion.

This approach creates two options, neither of which is an argument: Phil may see that actually it does work with X, or the other person may see for themselves that it doesn’t. Both build capacity, not resentment.

Step 3: Pull back to see the context

This is really the biggest thing Phil has changed about his behaviour. In the past, his impatience made him lean in. Now he takes impatience as the cue to pull back, to lean back in his chair, take a breath, look out the window, relax.

He asks himself,

- “What’s at stake right now?”

- “Is this something I really need to jump on?”

- “Is there something more important to make a point about later instead?”

- “Will my jumping in now help the process for everyone?”

- “Am I just reacting to my pattern with this person?”

These questions let him see the bigger context in the moment, and help him not make waves where there’s no storm.

The key: Let your body advise you

The big question is, how does Phil remember to stop and follow these three steps in the middle of his frustration and impatience?

He listens to his body. He doesn’t watch out for impatience so much as he watches out for physical tension, fidgeting, hunching in his chair, crossing his arms. These are all signs of growing impatience, but are easier to notice because they’re physical. Then he can ask himself, “Why am I fidgeting?” Sometimes he’s just antsy, too much coffee. Sometimes it’s impatience. Then he has a choice.

(For more on ways to stop and remember your intentions even under pressure, click here.)

There are three practices of generous leadership:

- Generosity

- Curiosity

- Less Velocity

Phil was stuck in lack of curiosity and trying to make everything go too fast. Now he’s slowed down enough to ask questions and is generous enough to make space for other people’s process and understanding. He no longer pushes his leadership peers into decisions that won’t hold up. He plans to go back through their meeting minutes and notes for the year and expects to see that the rate of revisited decisions has dropped. Plus, he and his colleagues just feel better about working together. And that’s not trivial.

m Collins wrote a wonderful article about including with our To Do List a Stop Doing List. The Stop Doing List may in fact be the more important of the two. The To Do List is a powerful force in shaping our accomplishments, but Jim’s article inspired me to reflect that the list is just as powerful in limiting our accomplishments. When we set outcomes in advance, we are ruled by expectation and we rule out possibility.

m Collins wrote a wonderful article about including with our To Do List a Stop Doing List. The Stop Doing List may in fact be the more important of the two. The To Do List is a powerful force in shaping our accomplishments, but Jim’s article inspired me to reflect that the list is just as powerful in limiting our accomplishments. When we set outcomes in advance, we are ruled by expectation and we rule out possibility.