Captain John Beebe-Center was captain of the schooner HARVEY GAMMAGE when I sailed aboard her as Chief Mate, second in command. It was my first job on a sailing ship, and I had a lot to learn, especially about working hard. The HARVEY GAMMAGE was known in those days as the HEAVY DAMAGE. She was old and tired, and lots of things kept breaking. Capt. John wanted any ship under his command to look sharp, so the crew and I often worked into the evening hanging over the side painting, chipping at rust on deck, repairing worn rigging aloft. It was exhausting, tedious work, and I balked at the endlessness of it. I felt it wasn’t really our problem. The ship’s office should be paying for newer gear.

Captain John Beebe-Center was captain of the schooner HARVEY GAMMAGE when I sailed aboard her as Chief Mate, second in command. It was my first job on a sailing ship, and I had a lot to learn, especially about working hard. The HARVEY GAMMAGE was known in those days as the HEAVY DAMAGE. She was old and tired, and lots of things kept breaking. Capt. John wanted any ship under his command to look sharp, so the crew and I often worked into the evening hanging over the side painting, chipping at rust on deck, repairing worn rigging aloft. It was exhausting, tedious work, and I balked at the endlessness of it. I felt it wasn’t really our problem. The ship’s office should be paying for newer gear.

Capt. John thought I was a spoiled slacker who needed to learn that if the crew don’t take care of the ship, the ship can’t take care of the crew, and in a storm that could be trouble. He was right, and my attitude set a bad example for the crew.

Capt. John rode me pretty hard much of the time, and pushed me beyond what I thought were proper limits. We chafed against each other in a downward spiral of recrimination and resistance.

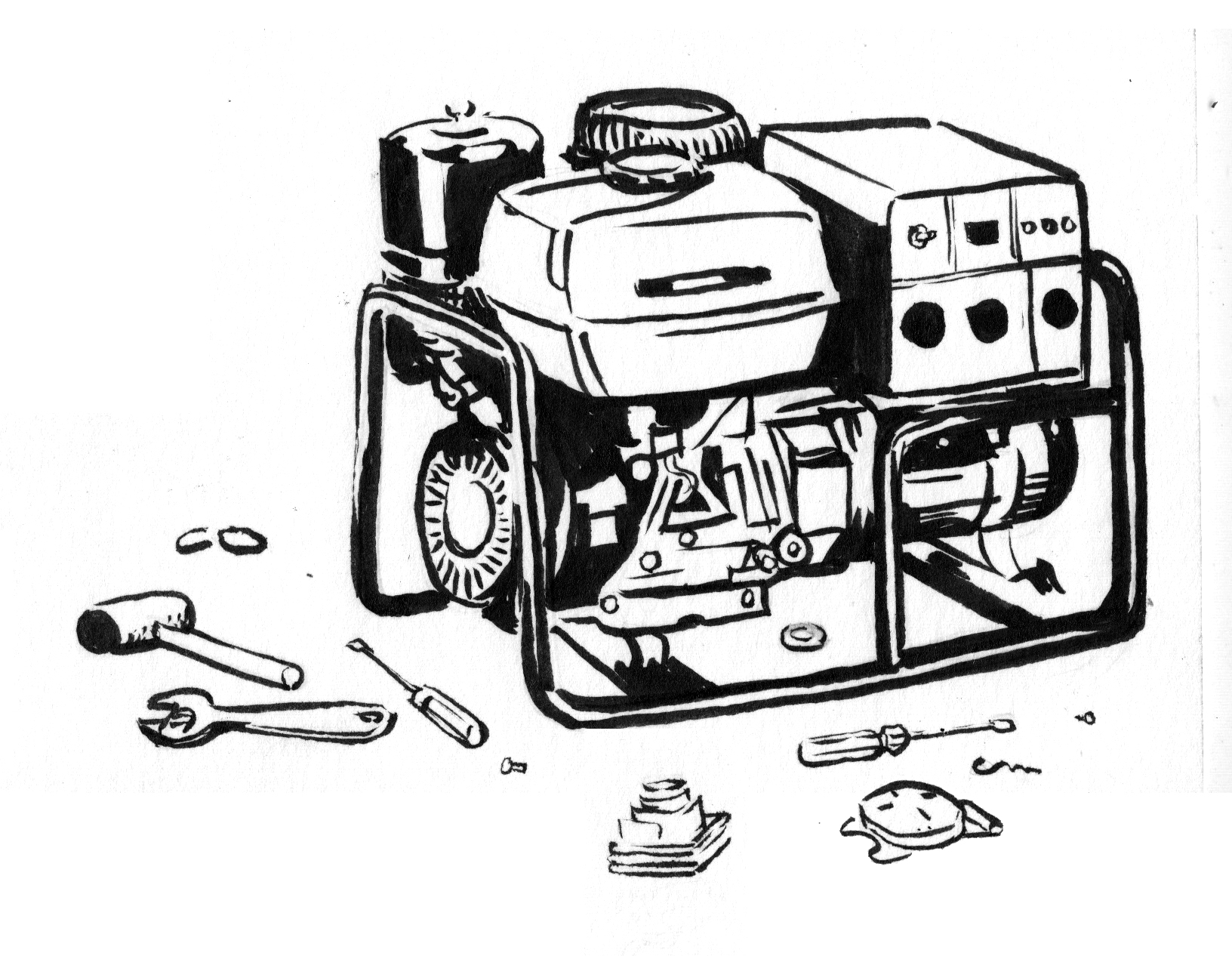

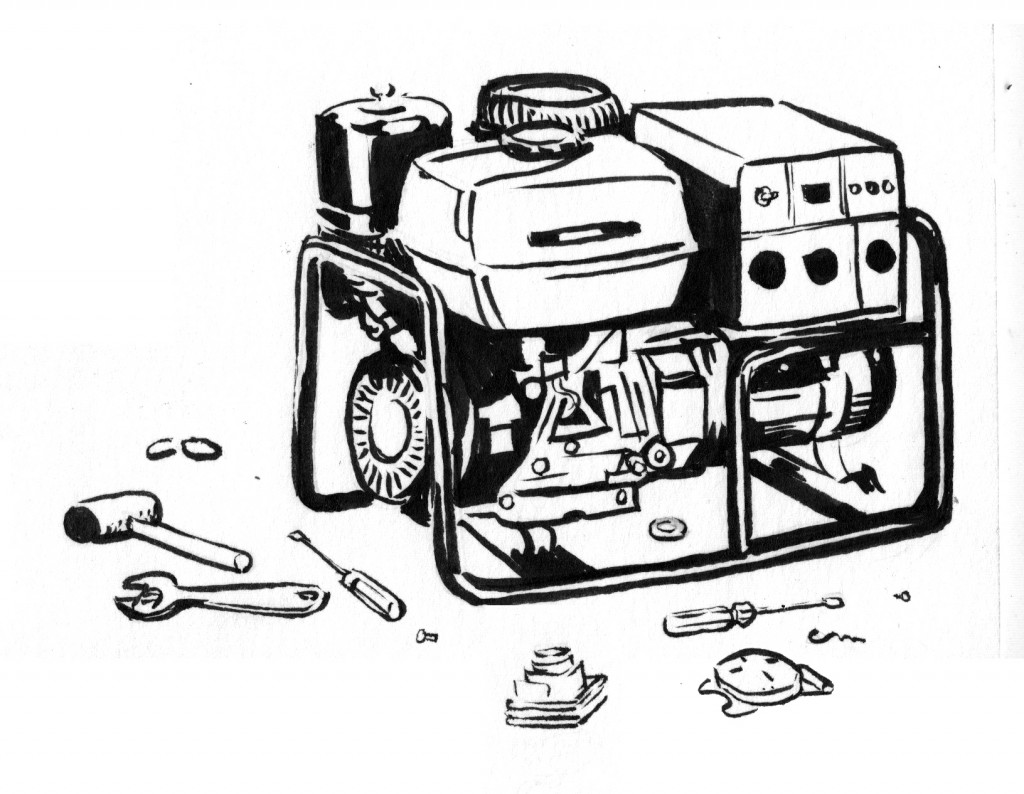

Then one evening at anchor, the electric generator that lived in a box on deck stopped running. Capt. John didn’t know much about engines, but he tried to fix it. I had the night off, and was getting ready to go ashore. John had the generator taken apart on deck and as I passed he asked me to hold a flashlight for him for a moment. I grudgingly did, and asked if he knew how to repair engines. He said no, but he might figure it out, and if it ran we’d save a lot of time and money getting it fixed. If it didn’t run, all he’d lose was an evening.

I couldn’t believe it. Why would anyone waste their time like this? We should just get it fixed in the morning by a mechanic. It wasn’t our problem, the ship’s office should give us better gear. But as I held the flashlight I watched him work. He was covered with grease, a couple of knuckles were bleeding, the daylight was fading, and he’d been crouched on his knees for an hour already. But he seemed content. He was gentler and more relaxed than I’d seen him before. Something about his doggedness, his private determination to do his best even if he failed, was suddenly compelling to me, and I saw him in a different light: not the unreasonable taskmaster, but the committed captain taking his responsibility seriously. I kept holding the flashlight.

We didn’t talk. I knew nothing about mechanics and had no suggestions to make. He urged me several times to go ashore for my night off, but I stayed. It was a clear, quiet night. Eventually he had the generator reassembled, and it wouldn’t run. He said, “Well, it was worth a try,” and went to bed. I went to bed too, but my view of work had changed. I began to see myself as Capt. John saw himself, as someone who could take responsibility for what was needed, and my resistance began to weaken.

The right kind of friction can cut through the ways that we’re stuck more effectively than someone trying to un-stick us. John’s earlier badgering had been the wrong kind of friction, more like chafe, and had only pushed me away. In contrast, his quiet doggedness was compelling, and caught my attention, so I could really see him, without worrying about what criticism of me I’d hear next. The friction I needed to wear down my resistance to hard work was John’s personal example, which, through the course of the evening, wore through my sense of my own limits. Even then, I would have resisted any admonitions from him about working harder, but he just worked away, and let me draw my own conclusions.

We often confuse chafe with friction. Chafe grinds us down, friction polishes our brilliance. Chafe entrenches whatever way we’re stuck. Friction wears through our stuckness. This friction can be gritty and rough, like the challenge of climbing a mountain or the long hours needed to take care of a ship, but it doesn’t have to be. Friction is simply anything that cuts through the ways that we’re stuck. Capt. John’s spacious, uncompromising example was just the friction I needed, and after that evening, we chafed against each other much less.

I’m offering a once-a-year opportunity to explore friction and chafe as leadership skills, at sea, during the Nova Scotia Sea School’s Professional Development voyage, September 17-21, starting from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Join me for this program for a broad range of people who lead groups: entrepreneurs, educators, corporate and government leaders, community development professionals. It’s a challenging adventure voyage mixed with leadership principles and discussion, and lots of learning from your peers. For more information, go to: http://seaschool.org/professional, or contact me at crane@cranestookey.com.