What are the conditions that foster a culture of engagement? What kind of leadership do you need to create them?

The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu summed this up more than 2,000 years ago when he wrote:

The bad leader is hated and feared.

The good leader is loved and praised.

The great leader, when their work is done,

The people say, “We did this ourselves.”

Here’s an example that inspired me at the time, and inspires me again in telling the story.

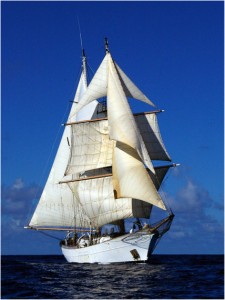

I once sailed with a young woman named Stephanie on the tall ship Corwith Cramer. The Cramer is a modern sailing research vessel that takes university students to sea for semesters of oceanographic science and seamanship training as part of their undergraduate degrees.

I once sailed with a young woman named Stephanie on the tall ship Corwith Cramer. The Cramer is a modern sailing research vessel that takes university students to sea for semesters of oceanographic science and seamanship training as part of their undergraduate degrees.

We sailed from Key West on a two-month voyage to the Dominican Republic, the Cayman Islands and back to Key West, taking scientific marine samples for the students’ experiments. We recorded the extent and condition of Sargasso seaweed (the Sargasso Sea is vanishing), the distribution of plastic debris, and so on. We anchored on Silver Bank, where the humpback whales come to breed, and lowered a hydrophone over the side with a speaker on deck to listen to the songs of the whales all night.

There were 18 student crew on the ship. At sea a third of the crew were on duty for four hours at a time, around the clock. Half were on duty in the lab with one of the scientists, while the other half, three students, were on deck, sailing and navigating the ship with the officer of the watch. If we needed more hands to handle sails or for some other maneuver we could call out the crew in the lab for a little while, but this 134- foot, 280-ton ship was operated most of the time by one professional and three students. People had to be pretty engaged.

As the weeks progressed the student crew became more and more proficient as sailors, and in the last month they started taking turns being officer of the watch in training themselves.

Late in the voyage Stephanie was the student officer of the watch off Miami, under my supervision. It was night and Captain Deborah Hayes had drawn a square on the chart away from the traffic lanes for big ships, told Stephanie to keep the Cramer within that square, and gone to bed. The organizational goal was set; stay inside the square. To meet the goal, the crew would have to do a good deal of tacking back and forth, maneuvering the ship.

One might have expected Stephanie, relishing her new competence and trying hard to fill the role of ship’s officer, to begin by undertaking some kind of engagement activity to ensure she got the performance she expected from her crew. She might have gathered us all for a pep talk, told us what kind of “buy-in” was needed from each of us to succeed in achieving the organizational goal, maybe even threatened us with consequences if we didn’t collectively meet that goal. This might have been followed by detailed instructions about what each person should do and what the timing would be and so on, to guarantee that our actions would be aligned with her intentions. She was under pressure to look good as officer of the watch, and she might have thought that her supervisor, me, standing right there listening, would want to see her demonstrate that kind of strong leadership potential.

This might be the way of Lao Tzu’s “good leader,” wanting to be praised for her “leadership.” But when it came time to tack, Stephanie called the other crew out of the lab, gathered us all together and said simply, with an excited smile, “Places, everyone.”

The delight of the rest of the crew was palpable. Everyone suddenly realized that they, a handful of university science students, knew exactly what to do to tack this massive ship and could be trusted completely to do it. Everyone headed off to handle a sail, with Stephanie’s excited smile shining on their faces too.

Stephanie didn’t make maneuvering the ship about her and her leadership. She didn’t make it about the organizational goal either. She made it about the crew. She made it personal. She recognized that the crew’s goal was not simply to follow Captain Deborah’s orders, or to be skilled sail handlers, or to work together as a high-functioning team. Those things did appeal to them and could be engagement points. But what they really wanted was to be Sailors; the kind of sailors that could tack the ship on their own, with nothing more said than, “Places everyone.”

Stephanie was obviously excited about being a Sailor herself, and understood her crew’s aspiration. She also understood that by trusting her crew to know their job, she made them want to be trustworthy. And she knew that when it comes to leadership, very often, less is more. We maneuvered beautifully and tirelessly inside our box through the night, and everyone brought their personal best to every tack.

When you hear this story, do you think, “Wow, we could do more of that?” Or are you thinking, “That would never work with our people?” If the latter, is competence lacking, or is clarity lacking, or something else? What would it take for people to say more often, “We did this ourselves?”