We often look for inspiring things “out there” someplace. An inspiring speaker or book, a Facebook video, a story of someone else’s accomplishment. But if inspiration is always found someplace else, then it’s always a struggle to go find it. That’s a problem.

We often look for inspiring things “out there” someplace. An inspiring speaker or book, a Facebook video, a story of someone else’s accomplishment. But if inspiration is always found someplace else, then it’s always a struggle to go find it. That’s a problem.

Here’s how to make inspiration ever-present and accessible, in what’s around us all the time.

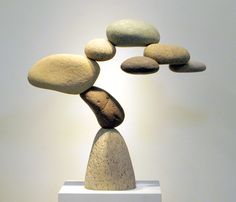

Prof. Eduard Franz Sekler, an old-world Austrian gentleman who is one of the patriarchs of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, had a rock. I took a seminar he taught when I studied architecture (a previous life).

At the start of class Prof. Sekler would set his papers and notes on the table and put his rock on top of them. We could tell by the way he placed it each day that he was very fond of his rock. Though we didn’t pay much attention to it.

One day Prof. Sekler asked us to consider how the design of things can influence the way we experience our lives. He picked up the rock and handed it around to us. We all held it, felt it, admired it. For the first time we really paid attention to it.

He then took the rock and stood it up on the table. It had always lain flat on his papers, but it had a smooth end we hadn’t noticed that let it stand upright. It shifted from mere rock to “object,” and we admired it afresh. He moved the rock to a tall stand that had been sitting in the corner of the room all semester with nothing on it. Given this place of honour, the rock was now the most interesting thing in the room. Finally, there were track lights on the ceiling that we didn’t generally turn on, but Prof. Sekler flicked the switch and the rock was spotlit against the wall, casting shadows and reflecting light from unexpected facets. It had become sculpture.

We all burst out laughing with delight. The rock was so much more than we thought. We applauded the rock for its achievement, and we felt suddenly good about the world, optimistic and appreciative, eager to accept the rock’s invitation to see more in ordinary things.

The way we experienced our lives in that moment suddenly changed for the better, which was the answer to Prof. Sekler’s question. We had been looking to the great architectural achievements of others for inspiration. But the inspiration we needed, to see things with a fresh eye, to appreciate detail, to take a creative risk, was sitting right there on Prof. Sekler’s papers all semester.

This was one of Prof. Sekler’s great leadership skills, to show us how to stop looking elsewhere for what we think we lack, and to look to ourselves and the things we already have around us.

A great teacher and a great leader are not far apart. As a leader, you can help your colleagues, your employees, your family, to draw on what they already have, which is always more than we think.

Here are some useful links:

To read more on the leadership power of ordinary things, click here.

To read about a simple way to inspire a workforce, click here.

![STRAW HAT[1]](http://cranestookey.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/STRAW-HAT1.jpg)

Engagement is all the buzz these days, but it’s not enough for people to be engaged. We have to keep asking, “Are we engaging people in the right things?” Often our focus on “engagement strategies” undermines the performance that’s really needed.

Engagement is all the buzz these days, but it’s not enough for people to be engaged. We have to keep asking, “Are we engaging people in the right things?” Often our focus on “engagement strategies” undermines the performance that’s really needed.

We had one huge fender on board, a giant inflated ball that we hung over the side to keep the ship from banging against a wharf. Carl grabbed this fender and ran to the anchor with it. I shouted to him to get back, the collision might well break the lashing lines and throw the anchor back onto him, which could cause a serious injury. Carl paid no attention, and laid himself out across the anchor to hold the fender in place over the point. It hit the fishing boat, compressed and burst with a bang. The anchor leapt up a few inches off the rail but did not break its lashings. Before it burst, the fender’s compression deflected our momentum just enough to let us graze past the fishing boat and float gracefully into our berth.

We had one huge fender on board, a giant inflated ball that we hung over the side to keep the ship from banging against a wharf. Carl grabbed this fender and ran to the anchor with it. I shouted to him to get back, the collision might well break the lashing lines and throw the anchor back onto him, which could cause a serious injury. Carl paid no attention, and laid himself out across the anchor to hold the fender in place over the point. It hit the fishing boat, compressed and burst with a bang. The anchor leapt up a few inches off the rail but did not break its lashings. Before it burst, the fender’s compression deflected our momentum just enough to let us graze past the fishing boat and float gracefully into our berth.

Of all the teachers that live along the South Shore of Nova Scotia, the most profound for me may be the Great Blue Heron. The Heron understands the interplay of stillness and action, and I learn a little more about that every time I see one.

Of all the teachers that live along the South Shore of Nova Scotia, the most profound for me may be the Great Blue Heron. The Heron understands the interplay of stillness and action, and I learn a little more about that every time I see one.

Captain John Beebe-Center was captain of the schooner HARVEY GAMMAGE when I sailed aboard her as Chief Mate, second in command. It was my first job on a sailing ship, and I had a lot to learn, especially about working hard. The HARVEY GAMMAGE was known in those days as the HEAVY DAMAGE. She was old and tired, and lots of things kept breaking. Capt. John wanted any ship under his command to look sharp, so the crew and I often worked into the evening hanging over the side painting, chipping at rust on deck, repairing worn rigging aloft. It was exhausting, tedious work, and I balked at the endlessness of it. I felt it wasn’t really our problem. The ship’s office should be paying for newer gear.

Captain John Beebe-Center was captain of the schooner HARVEY GAMMAGE when I sailed aboard her as Chief Mate, second in command. It was my first job on a sailing ship, and I had a lot to learn, especially about working hard. The HARVEY GAMMAGE was known in those days as the HEAVY DAMAGE. She was old and tired, and lots of things kept breaking. Capt. John wanted any ship under his command to look sharp, so the crew and I often worked into the evening hanging over the side painting, chipping at rust on deck, repairing worn rigging aloft. It was exhausting, tedious work, and I balked at the endlessness of it. I felt it wasn’t really our problem. The ship’s office should be paying for newer gear.